What do people want to be at age 100? The answer may surprise you

by Adam Felts

Half of all children born today in rich countries like the U.S. will live to be centenarians, according to one projection. Making predictions is a dangerous game, but there is a safer one embedded in there: many of us are likely to live a very long time, and probably longer than we would predict for ourselves.

According to one AgeLab study, the average age that Americans expect to live is 79 years old. Among younger adults, those ages 20-29, that number drops to 73 years old. The estimate of our younger respondents doesn’t even crack the average life expectancy in the U.S. today.

These estimates, frankly, are probably wrong for most people. There are many possible reasons why we underestimate our lifespans, but a big one, presumably, is simply our inability to imagine ourselves in later life. Ages 65 to 75 most of us can do – that’s the phase of life that has historically been designated retirement. The years after that, historically, have been relegated to decline and dependency, and they are typically imagined as mercifully brief.

But as people take better care of themselves, and medicine is better able to take care of us, those later years of supposed decline are turning out a lot better than people expect.

Preparation for old age often deals with questions having to do with managing changes in function and increasing dependence – how will my home support me as I age? Who will provide care? How will I get around the neighborhood? Important topics, but those questions by themselves are only half the story. The other half of the story is the fun half. It can be summed up in one question: who do you want to be when you grow up? All the way up? What does a good life look like at age 70? 85? 100?

The answer is probably different for each of those sample ages – they encompass 30 years of life altogether, the difference between age 20 and age 50. For those lucky enough to make it to age 100, there are likely multiple phases of “old age.” So we’re just going to focus on age 100

We conducted a research study in 2022 with Transamerica, a longtime partner of the AgeLab, on how people are embracing and preparing for longevity across the life cycle. As part of this research, we wanted to induce younger people to imagine what they would want their lives to be like in old age. In focus groups, the way we did this was by asking who they would look upon as their “longevity mentor” – a person who could function as a model for how they themselves would like to be in old age. They could choose anyone they wanted: someone they knew personally, a celebrity, a fictional character.

Some participants chose family, like a grandmother who, at age 95, was dating five men at the same time. Others chose celebrities and public figures, like Jimmy Carter (for his altruism), Queen Elizabeth (for her sense of duty), Toni Morrison (for the library of great books she kept in her apartment), or Tom Brady (who does not need explanation). There were also a few wild cards. One participant, for example, chose a guy named Carl who sells vegetables at a roadside stand outside of Seattle.

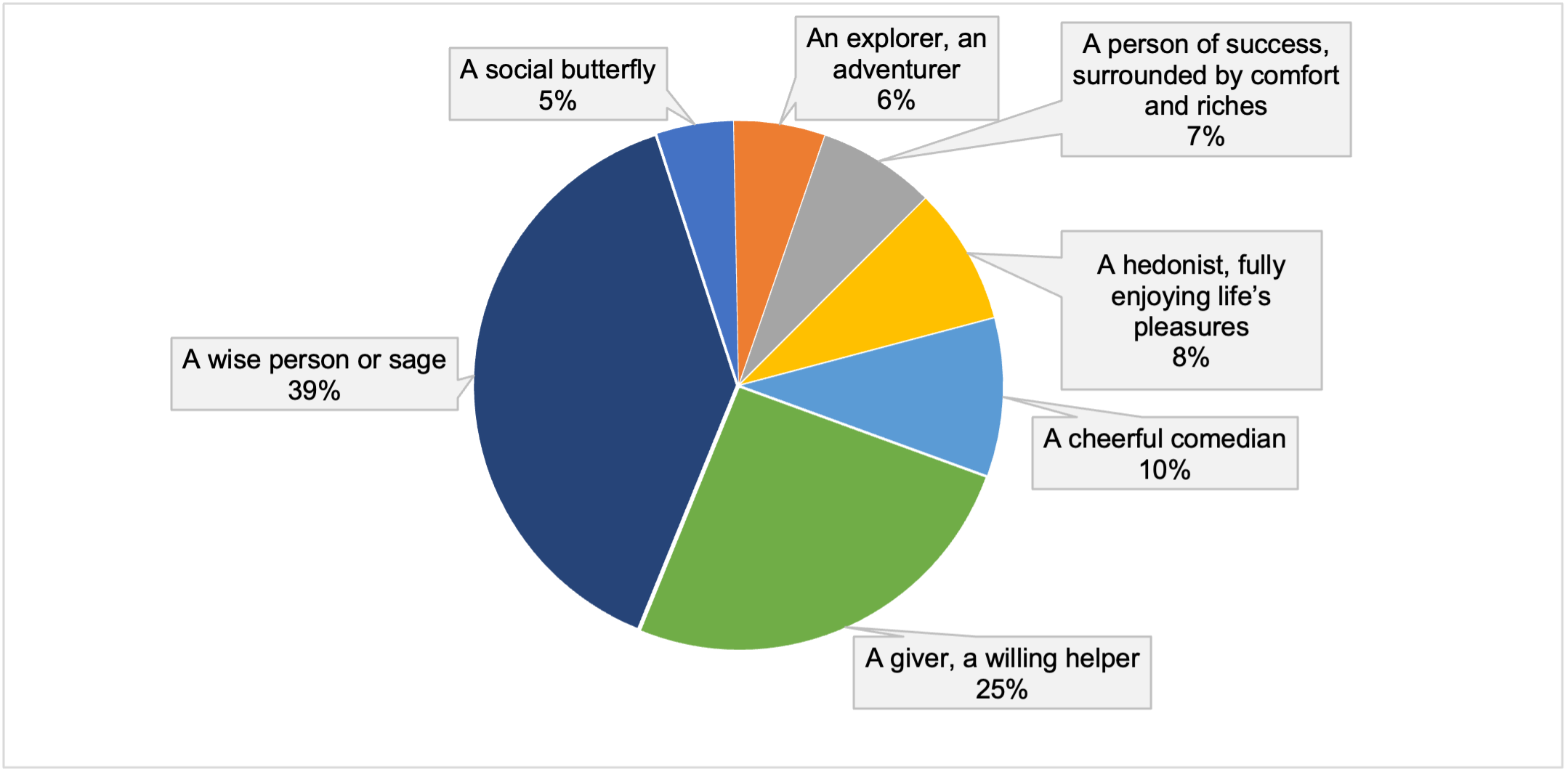

Then we took the question further; in a survey, we asked about 1,200 respondents to name the sort of person they would like to be at age 100. Instead of letting them name whoever they wanted, like in the focus groups, we gave them a prescribed list of options. To populate the list, we boiled down the longevity mentors we heard from the focus groups into archetypes: Jimmy Carter, for example, corresponds to “a giver, a willing helper.” We supplemented those with a few archetypes that were not reflected by the longevity mentors that people chose, but that encompass common goods that people tend to prioritize: money, pleasure.

The two most popular choices from the options we gave were “a wise person or sage” and “a giver, a willing helper.” Few people were interested in money and pleasure. Exploration and adventure, as well as an energetic social life, were also not very popular. Wisdom and altruism, instead, were the qualities that people most wanted to embody at age 100.

Again, these results might be different if we had asked people to think about their future selves at age 70 or 85 instead of 100. At age 70, for example, people might be more interested in seeing themselves as adventurers – a handful of years removed from the workforce, maybe, and still eager to do and see new things. That’s a question that might be explored with later research.

But these results tell us something very important about what people might hope for themselves at the extreme edge of the life course, during a phase of life that we might call—in line with a long history—elderhood. An elder is defined as an “an older member, usually a leader, of some community.” The leadership that an elder provides is a special sort: they hold memory of what has transpired in the past, and wisdom about what to expect in the future. They play lead roles in community rituals, especially religious practices and coming-of-age ceremonies.

No one of the archetypes above correspond to the elder role by themselves—but two of them combined come very close: the two most popular, the wise person or sage and the giver and willing helper.

The concept of the elder might seem quaint to our modern lives. The concept of wisdom might also seem relegated to antiquity or even fantasy—a word that we might feel uncomfortable using for fear that we might appear strange. Yet people are still drawn to it when they are asked to imagine their older selves.

The popular images we have at hand for retirement don’t often involve wisdom – they are more about adventure, hedonism, and comfort, qualities that turn out not to score well for people when they imagine themselves at the frontier of longevity. And when we think about what older adults need, especially the very oldest among us, we tend to think about more instrumental goods: accessibility, mobility, healthcare, comfort. But we may need to think some more about how we can provide opportunities for the oldest members of our communities to give back the treasures – chief among them, wisdom – that they have accumulated over their lifespans. That’s not an easy thing to provide, and may even require some dramatic social change, but it may be a key to realizing happiness in later life.